Anima Mundi, St Ives

19 July to 31 August 2024

Paintings are fascinating things. They have the potential to extend beyond imagery and the object hung on the wall as they provoke thought and, sometimes, a sense of common subjectivity, but with open-endedness and multiple yet authentic timelines. There can be a sense of not being finalised or prescriptive but suggest a more speculative, active domain of resolution. Arthur Lanyon’s exhibition at Anima Mundi in St Ives celebrates a three-year period of intensive work in the artist’s Penzance studio and these works have that sense of being both finished and in progress. It makes for a fascinating contradiction.

Whenever I visit Cornwall, thanks to the family holidays (close to thirty years now), a trip to St Ives is unquestioned. The first gallery visit is, almost certainly, to Anima Mundi. Way back when (the children were very young) it was the New Millennium and the Tate Gallery that drew us in to town. Anima Mundi has developed and matured and the quality of work displayed is consistently high and thoughtfully curated. Either way, this is the best independent gallery in St Ives. No contest. There really is no contest. This is a fact we should regret, as there are so many talented visual artists in, or linked, to Cornwall. There should be a dozen Anima Mundis in this non-London part of the British Isles.

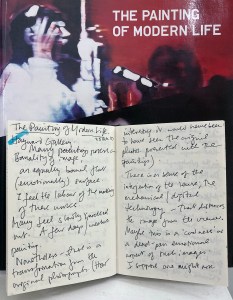

This is my first post-Covid visit to the town. Too long, I know. I have my Tate membership ticket at the ready – but it’s the Arthur Lanyon show, A Moon With A View, that tops my list of desires. I was not disappointed. With no intention to write a review, my partner and I have a good look around. There are three floors of displayed works to investigate but we are engaged in conversation on the ground floor for quite a while. We are attuning. No kids with us this year (we are a little sad and despondent). The conversation was quite formalist: line, mark, gesture, shape, space, surface, process, choice of medium – all that (important) stuff. It’s the way in we always take. As for subject matter. Not so sure. Not necessarily concerned. Not yet anyhow. Inevitably, the pen comes out of the pocket and I start my scribbles on the exhibition handout that I always hesitate to read before viewing the works it lists and promotes. This is my choice not to be too primed, although in retrospect Lanyon’s own commentary was very useful. For example, the centrepiece of the exhibition is the large work entitled, A Moon With A View, which sets up a frame of reference in his use of the term ‘shapeshifting’ that can be born in mind for any of the works displayed:

“The problem and solution to a lot of paintings is in the shapeshifting between background and foreground. In ‘The Full Moon Over Water’ by Turner, the painted waterscape represents the finite and the moon – seemingly painted but actually bare background paper – is the infinite. The relationship between water and moon – and, in my son Rory’s drawing, between tree and owl hole – draws the viewer closer to the non-material, further into the mysteries.”

And his use of the term ‘unfamiliar knowing’ in another extract also attunes the viewer:

“A childhood drawing can filter through your system like ‘chinese whispers’ and come out as something new. Call it an unfamiliar knowing… It is strangely intimate because the nature of the mind seems to expand inwards to a place that cannot be found in the world of objects.”

Drawings are embedded in the paintings. Surfaces are physically loaded and layered as well as scraped, scratched or sanded back. The canvas is a place of work. A place of purposeful action. Improvised and adjusted as he goes along, I would imagine. These certainly are hard won images. Drawings are crucial ingredients in Lanyon’s practice, collage too. His work can be described as gestural, abstract and certainly speculative and (dare I say) ruminatory through active image/mark making. They acknowledge an inherently cubist sense of time and space in a sense. Very real and encapsulating a nurtured progress through sheer hard work and commitment. There is no irony intended either and some content is childlike, not childish. Given time in an exhibition, and patiently letting the imagery in, goes a long way towards shedding unnecessary luggage. Which is what happens fairly quickly with Lanyon’s work. This may be because the works, of whatever size, are visually very busy, mysterious and demand the viewer’s undivided attention. I feel a sense of the everyday/extraordinary too. His commentary also spoke of the ‘moodboard’, which might well be a useful model for the true nature of narratives concerning the everyday simultaneously affected by the past and present – including long hours spent in the studio.

Fortuitously, I have just read painter, Rebecca Partridge’s recent paper for the Journal of Contemporary Painting in which she explores the post ‘Modernism/Postmodernism’ of the metamodern, which can be characterised by “Simultaneity, depth, a ‘structure’ of feeling and a return to meta-narrative.” This term includes subjective experience, authenticity, romantic subject matter and multiple subjectivities. For his narratives (which, like ours, can be solidly clear, barely recountable or obscure), Lanyon appropriates the physical, material world of the here and now. But he also includes familial memories, sometimes of an historical nature across generations, in a painterly present in which personal iconography is embedded and emerges to make highly engaging imagery. Like a movie represented in its entirety by one still – which perhaps only painting, songwriting and poetry can do effectively.

An initial impression of the exhibition was that this is good stuff. It’s not immediately obvious or illustrative. Why? The work seems kind of honest. I am not sure what this might mean right now even as I type up my reactions almost a week later. That’s good, or at least promising. Looking and, subsequently writing, is a journey of sorts, though you can travel backwards and forwards through the text. The writer might fool the reader into thinking that this was all a first draft. That’s not so easy with a painting. Painting is often a more conspicuous struggle. Painting is vulnerable to scorn or indifference and misunderstanding. Painting is a statement often unchangeable. It certainly cannot hide whilst on display.

Painting is sometimes ‘metaphysical’. What does that even mean? Emotions are in there, for sure, and some sense of transcendence. Is the metaphysical universal (too Jungian a definition?) – for surely, one should not need to read about Metaphysics to experience it? Definition follows experience. Aspects of this evolving theory, the metamodern, are here in Lanyon’s work too. To take just three examples, or traits, from Partridge’s article:

“A pervasive ‘structure of feeling’, a return to affect, to multiple subjectivities”; “Construction as well as deconstruction, the expression of sincerity and depth as well as irony or critical remove”; and “Re-engagement with historicity and meta-narrative.”

Refreshingly, in his work something of the child remains and is addressed almost naively:

“A boy draws a tree for the first time. It’s tall, no branches, just a trunk shooting up to a leafy looking cloud (all simple cartoons are the same). But he forgets what lives in trees: owls. Looking at the skinny trunk he decides to put the owl hole out on the left – a free-floating circle. He thinks his drawing looks good. So he doesn’t screw it up. His dad blue-tacks it up on the wall by the light switch.”

This approach produces a visual poetry of emotion generated by the personal memory and the mark making activity. This set me thinking about the marks we all make and our human ingenuity for language in all its manifestations. When language first developed was it from a gesture (body language) or a sound (made from the body) – or from found objects reconfigured for use? Anyhow, in time, a mark of some kind was made that carried meaning. With some sort of tool – the finger, a stick – we shall never now. But Lanyon’s practice conjures a form of the metanarrative from the instinctive urge to make painterly and colourful marks and shapes that will literally surface in the studio-based activity.

Unexpectedly upon leaving the gallery I found myself looking at the exterior walls and the pavement as a continuation of the paintings – an experience my partner confirmed for herself. This has happened before, but not often. This emphasises to me that Lanyon’s paintings are in and of the physical, playful and creative world, which is all around us and at all times.

Back home in Brighton I check my notes: “Battle between abstraction and fig. Not only visually busy but also content/lyrically.” That was enough to start writing this Rumination. How can one appraise artwork from a one-off visit? It’s more impressions gained than a sustained ingestion and understanding. But how do you separate the art from the viewer anyway? Paintings need a viewer, often strangers, not just the artist. We turn up with our tastes, our troubles, our pre-conceptions, misconceptions, expectations and prejudices, but ripe to be transformed and refreshed. Yes, refreshed.

Geoff Hands, July 2024

LINKS:

Instagram – @animamundigallery

Instagram – @arthur.lanyon