At Pippy Houldsworth, Heddon Street, London.

(From 8 September to 21 October 2017)

All images, ‘Courtesy the artist and Pippy Houldsworth Gallery’.

The last time an extraterrestrial was spotted in Heddon Street, Ziggy Stardust had arrived from Mars. It was 1972 and the hippy-trippy ‘60s were well gone. But, where the imagination was required, Sci-Fi (even when glammed up for rock ‘n’ roll) was still creating a futuristic mythology for audiences and the promises of other lands were appealing, if only someone might lead us there. Escapism, perhaps, but visual artists and writers (poets and story tellers especially) have always enlisted and augmented their imaginations to extend the boundaries of the sensible and balanced mind-set. Historically, this is the role of the Shaman in a multitude of guises and cultures and the notion of a purely rational consciousness is surely too much of a limitation to account for the scope of the mind.

Enter: Uwe Henneken. In reviews from previous shows, and from the press release for this exhibition at Pippy Houldsworth, much has been said of the shamanistic nature of Henneken’s fictive world of diverse characters and settings. His first solo show in London presents eight canvases, all completed this year. Entitled, The Teachings of the Transhistorical Flamingo, the exhibition showcases deceptively challenging imagery for his expanding audience. The work offers fascinating portals into a strangely familiar world – but where the inhabitants are out of the ordinary. Henneken’s troupe of exotic, cartoon-like or flamboyant beings, some glowing with inner energies, seems to either beckon the viewer, or a second character in the painting. The relationship of the viewer to the imagery is either one of invitation to imagine, perhaps in a dream-like state; or to encourage and provoke a more probing desire to make sense of the evidence presented.

Displayed slightly away from the central space of the gallery, but seen first on entering the exhibition, is ‘A History Lesson in Polarity’. This is the only landscape format canvas in the show and Henneken’s influences may have been affected by Paul Gauguin’s paintings, such is the sense of synthétisme in the implied narrative and settings. For example, at least three characters are subsumed into this rocky landscape (others are suggested with some sketchy use of pencil and paintbrush) and the figures and the environment merge as one undifferentiated fiction. Looking for something to make sense of, the animal on the left suggests The Lion King atop a rocky prominence, but the translucently white, big-eared creature opposite stares as if mesmerised. Overlaying the horizon line that might depict a raised escarpment, the young girl who will reappear in other paintings floats above an orange shape that might depict a field or a drawing of a bison from an ancient cave painting at Altamira. I don’t really have a clue – because the clues don’t add up. The lesson is a process, not a definitive statement of facts. Dream on.

As in the paintings that follow, the more you look the weirder it gets as a sense of initial comprehension is undermined by the various characters and beings who occupy these external spaces. A glance at the works before investigating close up immediately reveals a variety of environments. The inhabitants give them a narrative function integrated with the figures – even though these meanings might be unfathomable or deliberately open to interpretation. The various backdrops might be recognisable from personal experience (holidays abroad perhaps) because the scenery is not so otherworldly: starry night skies, mountainous vistas, rocky desert outcrops, and woodland or forest environments are earthly delights. These places provide the kind of theatrical or cinematic settings that we find in classic fairy tale illustrations from the past and popular, animated, children’s films for a more screen-engaged audience today.

In ‘Kin’ and ‘Transhistorical Waterfall’, appropriately hung side-by-side, the two figures appearing in each could be located in far away locations that are new to the viewer. An implied exoticism, most especially in the latter composition, where the colour and visual style shifts between a post-impressionist, illustrative and cartoonesque style, is sensed in the (possibly) masked and wild-eyed creatures. These two wonderfully colourful, but unidentifiable figures, stand either side of a narrow V shape parting of trees. Just beyond is a waterfall and in the far distance a youngish human visage peers out from the cliff face – but it does not feel like a joke or play on words. The viewer is invited to approach, delving into the jungle simultaneously, into pictorial and imaginative space. What appears delightfully decorative, slowly takes on a nightmarish feel – it will freak you out.

In ‘Kin’ [2017] a pair of wide-eyed creatures, arranged (on first reading) in a Mother and Child pose from the Early Renaissance period, merge into the Spaghetti western landscape. Incongruously, mum wears a pair of spotted tights and a red-gloved hand reveals the child’s face to be a flower head, not a plump infant. Their facial features and body hair merge into cloud and frilly costume alike. As with ‘A History Lesson in Polarity’ discussed above, my visual and mental confusion seems to increase rather than clarify. Why are the characters exploding in bubbling, billowing colour? Am I hallucinating in the desert? Or is the implied viewer who must complete the story on LSD?

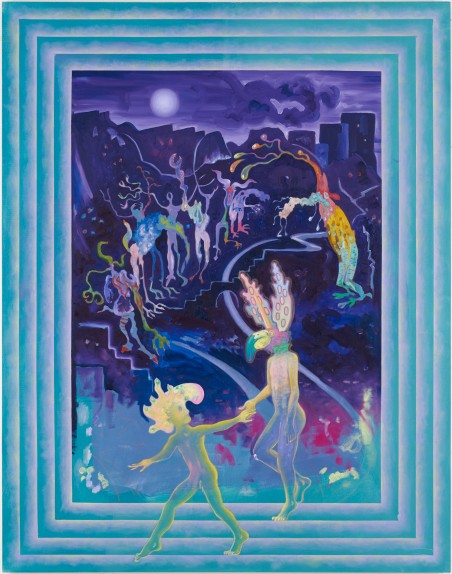

What might be a mediaeval castle in, ‘The Art of Jumping Timelines’ (the largest work here) also suggests the modern urban cityscape, where we could assume a band of party revellers are winding their inebriated way through the streets. But two foreground figures suggest another reading. A young male leads a taller figure away, out of the picture framed setting. Both wear strange headgear, suggestive of exotic animals and ancient cultures. Whatever the implied narrative, Henneken leaves it to the viewer to transcribe the imagery into some kind of understandable tale – albeit aided or mystified by the various titles.

Some images look complete, whilst others appear to be still in progress – ‘A Meeting at the Desert Shore’ is a case in point. The two foregrounded figures are ’coloured in’, as is the sunset and reflective surface of the lake backdrop. In between, the sketchy landscape appears to be reserved for the forlorn but glowing figure that observes the rainbow-girl and the Moomin character that gaze at each other. This latter personage might look quaint and child friendly at first, but closer inspection reveals a penis-like red serpent with three testicles hanging between his legs. This contradictory figure also holds a three pronged spear, or trident, which points down to the ground. If it’s a weapon it comes across as symbolic and ceremonial rather than menacing and its colouration from the sunset or the rainbow figure further diminishes foul intent. Perhaps two worlds are depicted here: one of colour, the other drained of unnecessary flamboyance.

Above a woodland scene in, ‘A Call’, flower-like stars appear amongst the woodland forms. They could be imagined as fruits from the trees or as stars beyond the earth. A sickly yellow mist cuts across the base of the huge blue trees. One tree has been felled, its purple roots transformed into claws that imply danger in this eerie setting. Placed on a pathway that leads into (rather than out of) this space for the imagination, stands the child from three other works on display, including ‘Space in Space’. As if against the light, in both of these particular paintings, she is almost featureless, flat and blue and has the same emanating glow that might be protective in some way. The stars revealed within her body shape in the latter painting are missing in ‘A Call’, but at the end of the curvaceous pathway is a golden light, which must be her destination. Whether she gets there or not might be up to the viewer to imagine.

In ‘Space in Space’ this cut-out figure appears to float in outer space whilst looking towards an implied planet or cosmic portal. The globe-like form to the left of centre is created by the Ouroboros – a serpent that bites its own tail – that symbolises the cycle of life and death in many cultures. The blobs of white paint within the inner circumference of the sleeping snake, its one visible eye closed, creates a planetary form – or an implied multitude of planets – and the white moon-like shapes are repeated within the human figure. Around these forms some of the stars resonate like wild flowers, creating a sense of animation. In this painting the notion of being at one with the cosmos (we are stardust after all) is implied. Contradictorily, because the meaning of the painting (including the title) might be the most obvious in the exhibition it might be limited by this degree of clarity. Obscurity or an implied, but unexplained, exegesis suggests a broader potential of meaning so that it is not fixed and holds more potential for the imagination.

As a phenomenon, the subject matter of Henneken’s paintings will surely appeal to an audience already interested in the likes of Rui Matsunaga, Raqib Shaw, or Chris Gilvan-Cartwright. A surreal, illustrative, narrative-heavy trait that enlists rather than rejects the past in contemporary practice appears fecund, alive and well. So, given the burgeoning problems of the world, whoever and wherever we are, we all may wish to escape somewhere at times. The shamanic spirit in any art form may not provide clear answers – but questions might prove more useful given our individual natures. That we experience inner and outer worlds simultaneously, and that the imagination is universal and timeless, might go some way to grasping the many potential meanings of Henneken’s paintings.

A final thought – in more recent times, the artist formerly known as Ziggy Stardust, asked: “Where are we now?” How apt.

Geoff Hands (September, 2017)