Gallery Dodo, Phoenix Art Space

26 April to 8 June 2025

THE PERSONAL AND THE POLITICAL

If you are already familiar with the artwork of Louise Bristow and Russell Webb you will know how fastidious they both are in the craft of their art making. Their respective and uncompromising working practices demand scrupulous attention to detail and full command of their chosen materials, processes and subject matters. I had not previously considered their work being shown together, but here they are in and other trivial matters at the Gallery Dodo in Phoenix Art Space. The results are impressive, not least because they have installed their work in complimentary fashion without either dominating the other and with a careful juxtaposition of contrasting imagery and objects. The works link under a broad still-life categorisation with the small (life size) sculptures sitting comfortably with the reduced scale of painted objects depicted in the paintings. As is typical of the still-life genre the imagery can be as straightforward, or as loaded, as the artist intends and the viewer is able to interpret.

My initial visit to the exhibition was hurried and fleeting as I had my own studio to get to at the recent Phoenix Open Studios weekend for the Brighton Festival. A few days later I was able to return to the space and to peruse the contents for as long as was necessary. But that first fleeting visit was surprisingly useful, for a stick had stuck in my mind. This was Russell Webb’s Stick Surgery (viii) to be precise. For when is a stick not a stick? When it’s a (found) curtain pole, with sawdust and acrylic paint applied, of course. But when this combination of materials is transformed, or re-naturalised, into an object/ornament that you might display on your mantelpiece at home you must remember not to be deceived and put it on the open fire – or you will have lost a sculpture. Why the mantelpiece? Well that’s where one might typically display a found object from a countryside walk. An objet trouvé become perdu (holding aesthetic value) – maybe with a hint of the wabi-sabi aesthetic. But it’s not a found object; it’s a sculpture, I dare say, of the unmonumental category. So whilst it references the natural and the everyday, the quotidian in contemporary artspeak, as a designed or constructed object it may have a different sense of value to the found object. At which point I am getting confused between any old stick and the one that the artist has made. Is this his intention?

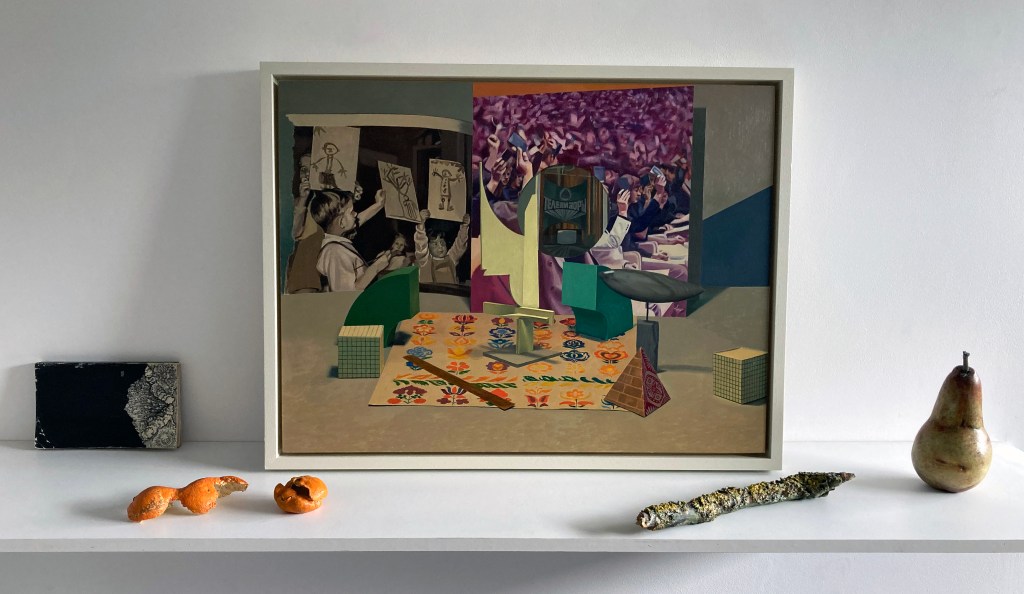

A mental fixation on just one piece of artwork encountered at the start of an exhibition is rare in my experience, as I have a habit to scan for an initial impression and to have a walk around to acclimatise myself. But as the Gallery Dodo space is relatively small, and I was pushed for time, this particular example of Webb’s selected pieces caught my attention first. Of course, in contrast to noticing this one individual item, I was also aware that, in a sense, the whole room was full of objects. In addition to the thirteen three-dimensional objects displayed on four shelves there were over forty still-life items represented in the four paintings. A return was clearly required.

Sitting in the Dodo space on my own for a private viewing a few days later was immediately quite calming. My inclination was to just relax and look, scribble a few notes as preparation for this review, and try to dismiss personal expectations. Simply respond to the physical content before me. Whenever I look at Louise Bristow’s paintings I slip into a state of calm anyway. They are so quiet, not even a hum emanates even if the imagery, a painting of a photograph perhaps, suggests a particular soundtrack from the contextual content. But this is not a display to sit and look at from a distance. It is imperative to stand up and move closer to each of the four groupings of an individual painting with various sculptural forms arranged on a shelf beneath the image. Both sets of work invoke an admiration of how they have been painted. In a sense, they are super-realist – though certainly not photo-realist. Webb’s sculptures might be termed as object-realist. They are utterly convincing as being the real thing, such as the orange peel or the piece of string. There is a common factor of the discarded, damaged or moving beyond some notion of a perfect state (e.g. Venus Figure – a slightly over ripe pear that appears to be tottering in terms of balance and tastiness) in his selection of reproduced items. They might typically be found in the kitchen, the garden shed, on the street or from that aforementioned woodland walk.

His titles are fundamentally important too: Lost Memory (a knotted length of material), Little Victories (two successfully removed orange peels that each remain as one piece of skin), or Family Tree, a broken off twig with three shrivelling berries remaining and the slightly spiky and pointed receptacle bases of the original flower where the missing berries developed. The titles can be nostalgic, jokey or deep. Aspiration (Manet) might reveal the aspiration of the young art student or the long-standing ideal of the older painter. His titles certainly guide the viewer towards a particular thought or interpretation.

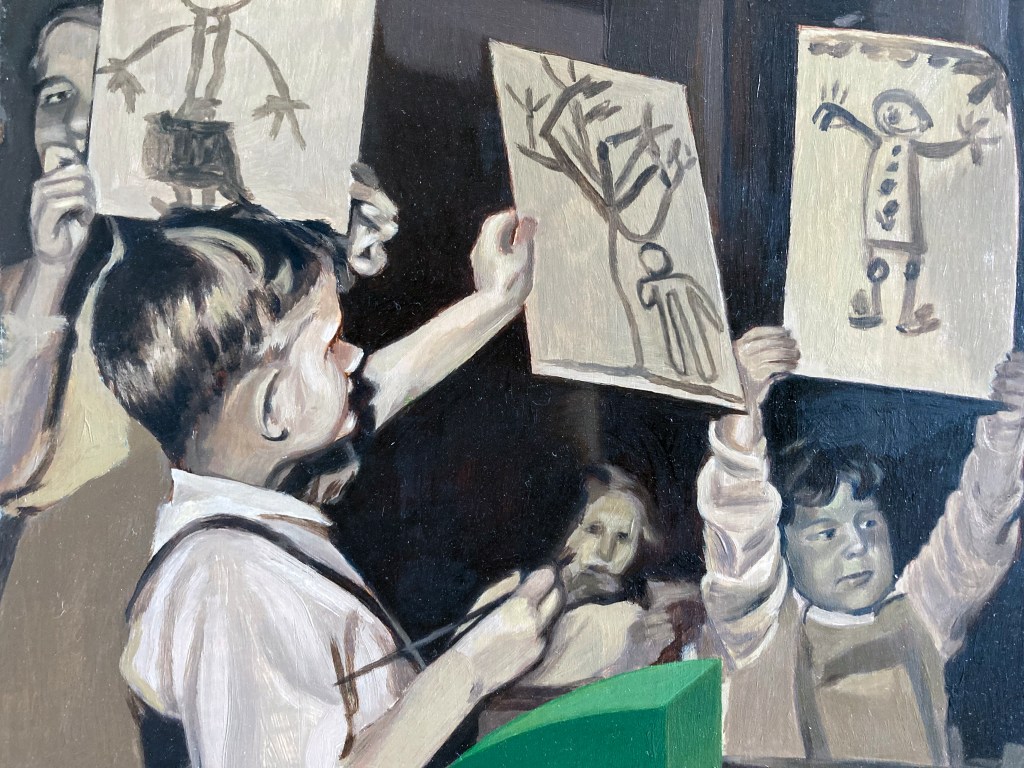

Bristow’s titles are also loaded with possibilities of analysis and exposition. There is also an element of nostalgia in the mid and eastern European and Soviet imagery where (for example) education, high-art, architectural design and social housing meet political idealism. On a formal level, the figurative-realist visual language of Bristow’s paintings appears to invoke that notion of apparent ‘reality’ that might align with objectivity. The People’s Forum, Red Vienna, Common Market and Playground are titles that certainly suggest further reading and investigation. But here, as paintings, and as objects, they invoke speculation and demand time for thought, probably over a long period of time. By implication, as observers of ‘art’ in a gallery, we might by extension question our own society today and critically consider our received political and social ideals and inspirations. But let’s not go down that rabbit hole now.

If one of Webb’s sticks remains in my memory, the image from Bristow’s paintings that stays with me is a section in the top left quarter from The People’s Forum that is a torn out page from a book or magazine. It re-presents a black and white photograph of a small group of young school children. Three of the four kids hold up their paintings for others to see and admire. The child (a girl?) in the top left corner of the composition looks at the photographer, and by extension us the viewers, so many years later. We might wonder who this person and the other young people were. What did they go on to achieve later in life, where did they live and what society were they were a part of. An objectively painted image (a reproduction) of a non-digital, black and white photographic print earlier reproduced in a physical publication might, semantically, become very subjective of course. It would also be a mistake to distance this image from the rest of the composition, visually engineered by the artist. What are we to make of another image of older (but maybe relatively young) people holding up small books? A few figures in the foreground are in focus with an out of focus background suggesting another photographic source, albeit in colour (maybe suggesting a later historical date than the aforementioned black and white photograph). Is that a sheet of wrapping paper on the tabletop? Does it introduce an element of nostalgia? What are those three-dimensional, architectural or modernistic objects doing there? Is that an ‘abstract’ type sculpture placed in the centre of the composition? None of Bristow’s compositions look random, in terms of content or compositional spacing. From the history of art, Piero della Francesca, Clara Peeters or the multi-talented El Lissitsky could well have inspired and guided her development as a painter – but she creates a voice of her own in the context of a politically complex world.

Physical objects (material culture in Semiotic theory) are inevitably reconstructed and interpreted by the artist and the observer, in this instance via the still-life repertoire and the notional gallery space that Louise Bristow and Russell Webb have all too briefly occupied. A sense of the personal and the political shifts between and within these works. As an audience we might question what visual artists do, and how they do it – especially the painters in a digital age. Biased as I surely am, seeing 2-D and 3-D paintings as impressively skilful as these, I sense an argument for the continued relevance of painting that both references a deep history and provokes or coaxes the imagination of the viewer. There may be more to this show than meets the eye. Where’s Duchamp, when you need him…

Geoff Hands

Links:

Homework/further reading Daniel Chandler: Semiotic for Beginners