Transformations: Robin Greenwood and Gary Wragg

At Linden Hall Studio, Deal

Heather and John Corley developed Linden Hall Studio into a gallery space in 2014 and a visit to Transformations provides a good excuse to get out of the city and head for the Kent coast. Gazing out to sea from any location enhances our physical groundedness (literally) and we get a reinvigorated sense of that weird but ever-present phenomenon called ‘space’. Extended space is curious because of our own limited human dimensions, from which we perceptively judge all immediate senses of distance, size and scale. Distant space can be observed with some sense of safety, even if temporarily, as threats draw near. Looking to the distant horizon, especially when the sea has replaced the land, can evoke a mysterious sense of future times and places. Close space, within arms length, holds love and fear in equal measure.

Spatiality in visual art, especially painting, also provides an extending experience for the imagination, and the trickery of illusion (aided by the sophisticated perspectival inventions from Masaccio and Quattrocento painting onwards) has permeated the reception and reading of painting for a long, long time. Likewise, abstract painting engages with this experiential, psychological and forcefully visual engagement with notions of space. Colour and linearity, to varying degrees, are often a component part of this spatial scenario and Gary Wragg’s paintings have demonstrated this over several decades.

Sculpture is another matter, where form (involving volume, weight, mass and monumentality), rather than an abstract notion of spatiality, has dominated its production and development. Anthony Caro changed all that in the 1960s, with the fusion of material (typically steel) creating structure in space – as space. Robin Greenwood was a student of Caro’s at Saint Martin’s School of Art in the early ‘seventies and so a loosely woven School of Caro (from the New Generation and beyond) might still be discerned at times, despite the endemic plurality of late modernism/postmodernism that has created a mixed bag of avenues and cul-de-sacs for artists to explore.

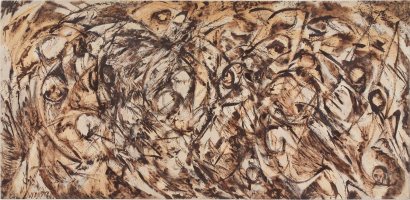

Gary Wragg’s formative painting education was forged at Camberwell and the Slade Schools of Fine Art, respectively. Wragg’s abstract expressionist influences are clearly New York School (Jack Tworkov and Willem DeKooning spring to mind) but his paintings are unmistakably identifiable as ‘Gary Wraggs’ and reveal his personal relationship with the practice of drawing and Tai Chi.

Wragg and Greenwood have evolved from the same generation and the Transformations exhibition, curated by Sam Cornish, provides a welcome combination of contrasting yet complimentary works. At Linden Hall Studio, the two exhibition floors are filled with natural and artificial light throughout the day. This light (as if it were a medium of the architecture) illuminates so effectively and is a feature of the gallery that presents the works exceptionally well.

For a first impression, two of Wragg’s paintings have been placed in the front windows to give a taste of what will be inside the gallery. Above, on shelves, are six of John Corley’s glass ‘muffs’, or cylinders, of coloured glass. These are not part of the show but also hint at the colour and light that is a major feature of Wragg’s canvases. Entering through a double door, two of Greenwood’s sculptures have been placed to either side of this initial space and are bathed in natural light from windows above, where a mezzanine floor opens up the gallery space. Four of Wragg’s large canvasses (plus a tight configuration of eight small compositions on card that are from the same series as the works in the window) immediately create an impression of qualitative choice and arrangement. Although the building was originally a chapel, there is a comfortable domestic scale to the space and a staircase that takes visitors up to the first floor, with two more sculptures and over a dozen paintings, including three more large canvases, further hints at this homely aura.

There is much to see (39 works in total) and the surprisingly roomy walking area on each floor allows the viewer to stand back to find the correct viewing distance for each work. Except where paintings are purposely hung together (essentially the smaller compositions), the indicative relationship between paintings and sculptures in adjacent spaces are neither forced nor dependent upon each other. In addition to the obvious contrasts between painting and sculpture, Wragg’s colourful and light (in tone) paintings, and Greenwood’s dark and heavy (in weight) sculptures, creates a balance rather than a confrontation between very different works. The larger canvases relate to the sculptures particularly well as they occupy similar characteristics of size and presence, though any links will be circumstantial rather than programmatically devised.

But whether intentionally or not, questions were raised in Transformations: Do we look at and experience abstract sculptures the same way as abstract painting? And are our expectations different? From this pairing for the exhibition both forms of abstract art contain a sense of rhythm and flow within their respective linear configurations. Each artist appears to work intuitively and without strict expectation of the final outcome in a spirit of freedom for what might transpire in the creative process. Both work in series (which can falsely suggest predetermined forms) and there is also a tactile sense of materiality of the mediums (of paint and steel) that counters illusionism and figurative forms. Greenwood and Wragg are committed abstract artists who have never waivered in their personal quests to develop visually emboldened works within the field of abstraction.

One distinction, which equates the viewer with the work (as much as the artist’s intention), might be in the way the work is looked at or apprehended. Greenwood’s sculptures, which are made to be engaged with visually, and experienced in the round, can be viewed either standing still and in movement. Momentary compositions, made from pausing to take in and consider the work, are endless as even the slightest readjustment of positioning changes how a three dimensional form is seen. In Greenwood’s sculptures there is a mysterious, subtlety aggressive, ‘Gothic’ persona to the works. This latter designation may be rather superficially attached, but the metallic darkness, the sense of weight and the uncompromising nature of hard metal, pertains to the uncompromising nature of the works, especially those suspended from the ceiling. Looking up at ‘Kwoke 166’put the bundle of steel (with a little wood and plastic) into stark contrast with the spotlights on the ceiling and felt quite menacing.

Returning to notions of spatiality, with sculpture that is big enough, the viewer’s own physical space is encroached upon. Is this where sculpture can surprise or unnerve the viewer? Like another being before them that activates real space – not just headspace. And as the viewer moves around the forms, careful not to walk into or too dangerously underneath, the changing compositional framing of looking can never rest. With the sculptures there is the issue of gravity too – especially potent for Greenwood’s suspended forms. But also of weight, which in ‘Tree of Ornans’, lifts defiantly from the level of the floor with dexterous and agile movement that is surprisingly lyrical, as the fragmented industrial component parts become gestural branches suggesting arms and legs. It is balletic and poised.

Interestingly, Greenwood’s three suspended sculptures contrast with ‘Tree of Ornans’ more than with Wragg’s paintings. There is a tighter configuration, in the almost head-like suspended sculptures. The allusion to the head probably has more to do with their positioning off the ground/floor (131, 138 and 166cm). The viewer meets these pieces head-on, rather than at knee and chest level with the ‘Tree of Ornans’. The physicality of the sculptures fixes the implied bursts and movement of stilled implosion/explosion and rotation. By contrast, it is the viewer who must move around the works. The viewer becomes the kinetic component in a spatial performance.

With painting there is an obligation to stand still, rooted to the spot. The viewer’s eyes, and sometimes the head, will move as the gaze surveys and wanders. Abstract (visual) space will take the viewer in to its implied space, with the flat canvas surface as counterpoint. Wragg’s paintings, typified by his signature gestural calligraphy, instinctive and freeform colour combinations, and (almost) dangerously undone configurations of marks and shapes, are always expressively lyrical. The kinetic features are in the painting’s virtual space. The viewer is a little more physically passive.

‘PL5’, exhibited downstairs and ‘OTBDG, 2, Yellow’, shown upstairs, are two works of Wragg’s that could be juxtaposed with the sculptures as there seemed to enough air around the gestural configurations to describe forms in space. Behind and within a freeform dance of linear gestures, Wragg creates a sense of shallow space. But in each work various colour patches, splatters and gestural swirls sit on the surface of the visual field to deny the illusion of concrete, representational form.

I suspect that, by convention, the viewer does not look at abstract sculptures in quite the same way as abstract painting because expectations are different. Paintings suggest physical, geographical distances and ‘otherness’. Because of illusionistic functioning (‘picturing’) and inherent subject matter (“what/where is it?”), painting is somehow conjured from virtual realities. But sculptures are more overtly, formally, here and now – occupying the viewer’s own physical space. Does the viewer meet a sculpture – and observe a painting? Whatever conclusions can be made, Transformations poses questions that do not have to be answered with certainty, just as abstraction is far from over as a major genre in contemporary art.

All artwork images © Robin Greenwood or Gary Wragg

Links:

Linden Hall Studio –

https://lindenhallstudio.co.uk/current-exhibitions-at-linden-hall-studio/

Sam Cornish discussing Transformations at Linden Hall Studio –

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_MYjVLdFjWo

Robin Greenwood –

http://www.poussin-gallery.com/site.php?artist=15

Gary Wragg –