At Phoenix Art Space, Brighton

1 March to 13 April 2025

Often the best paintings, literature, music etc. take time to come through. The first impression may well be the one to not give too much credence to. A degree of complexity in any art form deserves a period of further thought. After five or six visits to Grant Foster’s exhibition at the Phoenix Art Space I know that I need to look again and again. This is good.

Q. What do you think about when you are looking at an exhibition of paintings?

What is the mind of any onlooker doing? Searching for something recognisable? Prepared and preconditioned by our shared culture we might be expecting something general or commonplace, such as a human figure, a landscape or objects constructing a narrative as a way into the work. What, potentially, could these visual references add up to? What might the storyline be, if there is one? And if the narrator/artist is describing something, making a serious statement or spinning a yarn, can you relate to the theme? Alternatively you might be more of a formalist with an eye for the aesthetic hit. The purely visual, via systems or improvisation, might be your thing. Either way, so-called content can be very complex or minimal. Of course, if the exhibition has a title you are already geared up with some expectations. Home To My Teenage Bedroom sounds perilously loaded.

There may be some idealised notion of preparing to see an exhibition as objectively as possible with the mind emptied. Ideally the extraneous thoughts of those other aspects of one’s life are put aside, at least for a while. It may be an artificial approach, but imagine entering a show with a mental blank slate. No preconceptions or expectations. What is experienced afresh? Nope. This is just not possible, or even desirable. Our various histories create our personalities (however flawed or enlightened) and enable a personal take on what we see and understand. In the case of this show we might consider that that teenage past was an under investigated portal that might throw some light onto who we became in adulthood. Grant Foster acknowledges this potentially rich period of life in a wall statement:

“It’s often said that our teenage years are the most decisive – our interests, obsessions, and passions are innocently formed and planted like seeds, taking root over time.”

But without any foreknowledge beyond the title of the show, visiting Foster’s exhibition at the Phoenix Art Space initially left me more impressed with the thoughtfully and dynamically prepared arrangement of works by the artist with the new Phoenix Art Space curator Laurence Hill, than with the paintings. I made no connection with the content, despite knowing the title of the show. I was surprised and sensed that this was a body of work requiring more viewings. In retrospect I guess I was a little overawed by the presentation. But I sensed that a few visits might be necessary, if only because my thoughts were probably too elsewhere – especially at an opening event that was extremely well attended as the crowds flooded in for three painting exhibitions under one roof.

Back home at the computer keyboard I recalled my first visit, and an all too brief second pop-in the next day, by describing, albeit generally, those initial impressions. The earliest typed out observations prompted the following text:

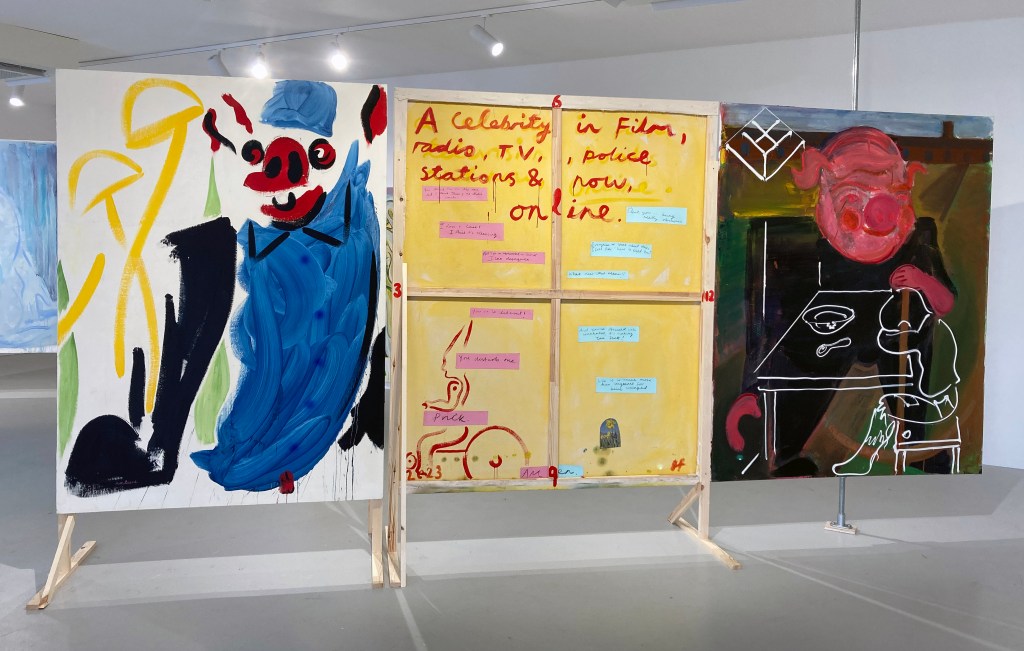

The visitor very much walks into this exhibition. Into a structured, planned space – but not forced, obliged or coerced to travel in a particular way. This installation invites a weaving, walking, stopping and starting, slow dance in, around and even through the works. In the large main gallery the majority of the fifteen paintings are free standing, fixed on wooden structures that are equivalent to the human scale. Some have vertical poles, like spines, attached from floor to ceiling to prompt the visitor to actually touch the work of art and to carefully turn it around, thereby opening a door of sorts and changing the arrangement where, in two instances, accompanying canvases are set up next to each other as a triptych…

But I was clearly missing so much more. On my third visit I found myself tuning in to the echoes of the art historical that, generally, permeates all contemporary painting. Plus, the painterly visual language and the way that Foster generally draws with the paint media – perhaps as an expression of his personality – was immersing me into the imagery. For example, in the four St. Francis paintings, representing statuesque Giotto-type figures that are placed as two separate implied diptychs on the walls, the paint application is fluid and almost shorthand. The figures have turned away from the viewer. Are we to follow – through some kind of portal? Then there is evidence, no more than implied, of other figurative content. A cat in one composition and a swan in another. There may be some wings too and a building type passageway where there might otherwise be legs. Is there a rural environment too, with a little taste of landscape beyond? The uncertainty must be deliberate.

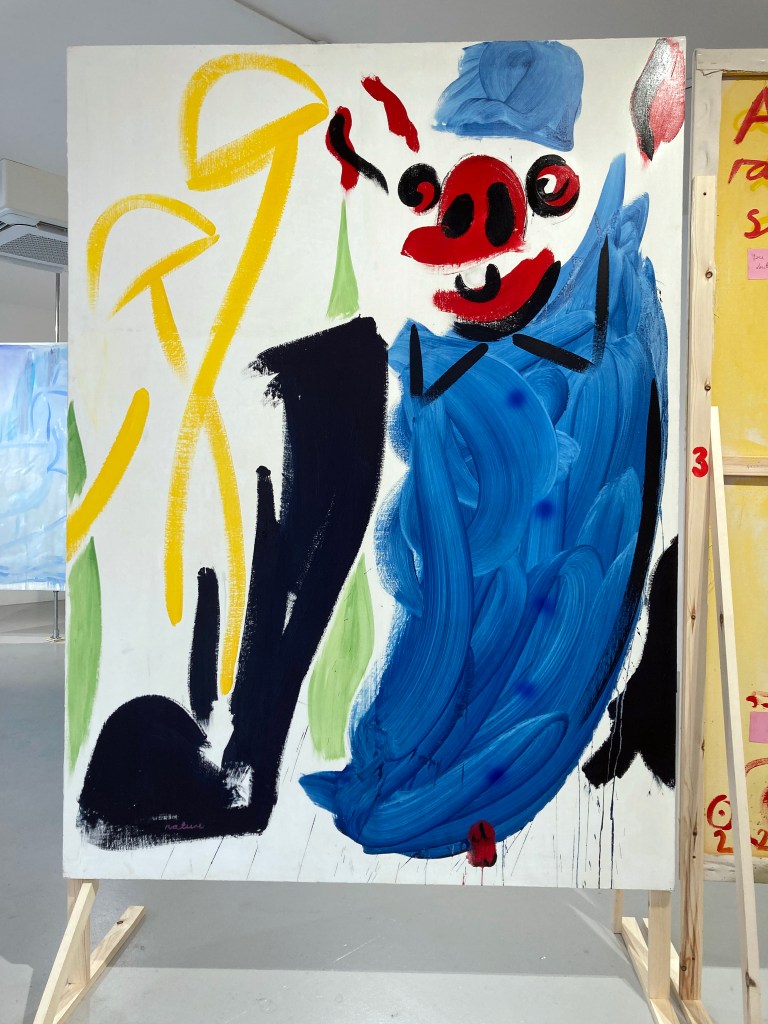

Another art historical reference might be the Sotheby’s work shirt fixed to the reverse of one of the freestanding canvases, Nature V Nurture, to suggest the Crucifixion. Perhaps I am reading too much into this, but others have made the same conclusion. On the front of this canvas a cartoon-like figure dressed in blue, but with red and black facial features appears animated by what might be two large yellow (psilocybin) mushrooms. This could be a retrospective self-portrait. It may not matter. Already, external contexts (facts or fictions) are expanding the reading of the works, even if I am mistaken. I am thinking again about the almost sketchy way that Foster applies the paint. In some of the works, many of them in fact, there’s a slightly underworked feel to the painterly execution, as if too much effort is to be avoided. This equates to a notebook-type intention, a formal device, which I interpret as a reference to a way of thinking and to the nature of mental recall. Events of the past, however strongly remembered or not, become a form of visual shorthand. Yet two canvases in particular stand out as comparatively overworked (even if they are not). These are Psychiatric Hospitals, Full, No 3 and Queendom which are each a part of two different floor-based triptychs.

Each of these compositions appears quite different in subject and imagery. The former depicts a building (the hospital?) in mid-distance with a bloated pig-like character in the foreground, stood behind a table where a sad child sits with a discarded spoon and an empty bowl. In the latter, foregrounded figures appear to be involved in a judo move. Like the boy and table in the other painting these grappling forms are created with a squeezing out of white paint straight from the tube. Despite the two contrasting painting styles this incongruity works.

Queendom is the more complex, visually loaded image. Over time the observer will make out other forms including a naked figure in the top left corner (which reminds me of figures from both Titian and Matisse); two animal forms (formerly cartoon characters from a childhood comic book?) and even a flat smiley face symbol, albeit with a nose, just below the centre of the composition but in shadow. I am sure that there is more here to emerge from a ghostly, shroud like confusion that threads throughout the composition. The looking experience is truly durational, suggesting that more could well emerge.

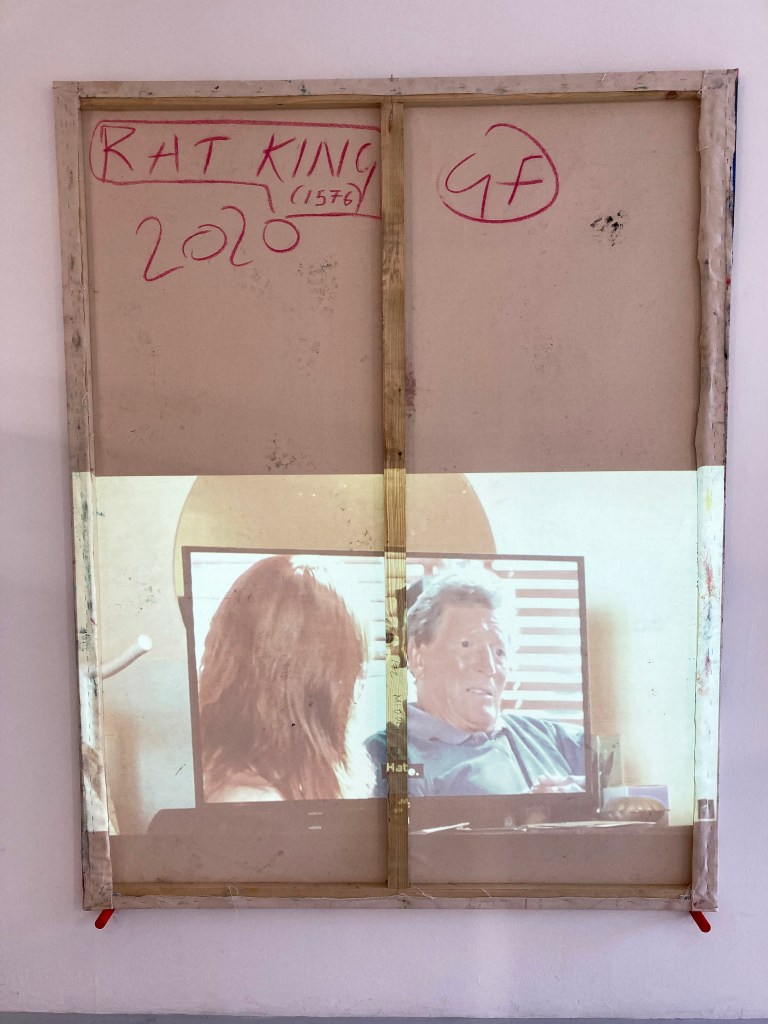

On this time-base note Rat King (1576), which has the de facto front pressed to the wall, adds a digital layer provided by the projection of the Telly with Mum video repeating every 43 seconds. This small element of the digital might be a pointer to future developments in Foster’s work – or a remnant of a past engagement with the once trendy art college digital projections that can be somewhat passé. But the projected content does provide a moving image element of collage that references watching television, which was the precursor to the computer screen and now the mobile devices that cling to our hands like an extra organ, back when Foster was a teenager.

Which brings us to a literal emergence: the backs of the paintings. The majority of the works have backs to be viewed as additional fronts, which will be an interesting challenge for collectors of Foster’s works. The convention of writing a title and adding a signature on the reverse of the canvas is developed from what might be seen as the private space (like a sketchbook or a notebook) that actually wants to be quite public. With the further addition of painted imagery, photographs and extended text, they are clearly beyond being auxiliary or supplemental to the conventionally expected paintings made on the front of the canvases. The stand out rear view to me was on Help, which included a small printed image of a daffodil, a painted pixie-type figure riding a bicycle, a possibly alternative title (‘A celebrity in film, radio, TV, police stations & now online’) and a conversational collage of hand written text that was a recalling of a conversation between the artist and his partner. Foster’s jokiness feels deadly serious.

But delve further. Beyond this environment of paintings on the floor and walls the visitor, as a possible means of escape, enters what (in retrospect) may have been the implied bedroom of the artist’s youth. An annex off the main gallery with a large wall displays at least two hundred (I wasn’t counting) drawings, paintings, written notes and printed reproductions on paper. I jotted down a few of the phrases: Love and fear, All life is innocent, I must be the victim of a Hallucination, Innocence, Be Good People, and my favourite: MEMORY IS WHAT DOESN’T DISINTERGRATE (sic). Pictures (from books, art, TV, newspapers, magazines and the Internet) are so important to us all – and virtually unavoidable, then and now. Imagery from all and any context feed the imagination. There’s a sense of being inside an image-based thought process in Foster’s work that is constantly nourishing the potential of what the formative and the now fully realised artist continues to imbibe and assimilate. It’s the magical ordinary extracted from an image and text obsessed world – that was surely first started back in the caves of pre-historic humankind when the fundamental technology of mark making and visual language was really no different to now.

Foster’s wall text at the entrance explains more about the accumulation and assemblage of text and imagery:

“My studio is a haptic, experimental environment, where I continue to collect images, organising through free association: drawings, phone-screen grabs, newspaper clippings, children’s book illustrations, advertisements, and fragments of text.”

So, if the teenage bedroom was a place of seclusion that conversely expanded the imagination, then the adult studio clearly continues this function. Connected to thoughts and memories a touchy-feely collage type process, aided and abetted by literal touch as imagery that can be moved around, has expanded to and created the paintings in this show. On a more universal level we, as viewers, can surely connect with this phenomenon of the imagination, which runs alongside the everyday. Like the artist, we are always reconstructing and re-remembering: memories of memories, whether it was earlier today or decades ago, the happy and sad places, the images we made/make and those that we receive voluntarily or not. Narratives may not always be trusted as truth but new meaning or continuing misunderstanding may be of greater value and emotional impact as we age.

At this point as I consider wrapping up this review I recall a reoccurring image from the exhibition. There is just one photograph reproduced in the publication, A Year of Kindness that Foster has published and presented as the first listed work in Home to My Teenage Bedroom. It shows (I believe) the artist’s mother and uncle standing close to water where a swan has approached. The image is first encountered in the exhibition in the painting entitled ‘Panspermia’ (which Wikipedia informs us “is the hypothesis that life exists throughout the Universe, distributed by space dust, meteoroids, asteroids, comets, and planetoids…The theory argues that life did not originate on Earth, but instead evolved somewhere else and seeded life as we know it.”). The image crops up again on the amazing collage wall of imagery in what must be a preliminary drawing for the painting later on. Now there are four swans, curvaceously morphing into organic shapes. The drawing could easily have been missed amongst so many images, but may have stood out for its line of handwriting at the bottom of the page: “all life is innocent”.

Returning to the painting, Panspermia, one sees that the swans could be read as decorative visual elements and that the black lines in the earlier drawing are now changed to a more yellowish green hue that visually suggests an organic environment. The branch of a tree fills the head shape of one of the two figures. Is that a wind farm sail in the top left hand corner that hints at the environmental concerns of today? It makes for a somewhat dreamy image whereby the unconscious is given as much credit as anything rational.

Near the start of my response to this exhibition I posed the question: What do you think about when you are looking at an exhibition? Perhaps, what you and I think about after seeing an exhibition is more pertinent. Our memories of previous experiences, times and places are embedded in our imaginations as we engage in recall. There might be hidden treasure in a photograph album too. Timelessly it’s all a here and now that, for some, becomes stronger as we get older. Foster provides much for the viewer to consider. Nothing is necessarily too clear to merely illustrate. This project sets us up. The viewer has work to do.

Geoff Hands (March 2025)

LINKS: