Towner, Eastbourne

29 November 2025 to 25 January 2026

Visual art is never totally a form of escapism, even if a gallery visit takes us out of our ordinary, everyday for a while. In the UK we inherit a long-standing interest in the represented landscape and the people and places therein. Stepping into the temporary exhibition space on the ground floor of the Towner the visitor, like me, who essentially was there to see the J.M.W. Turner watercolours on display in Impressions in Watercolour, might already have felt more than satisfied with their visit having viewed a multitude of landscapes either aesthetically breathtaking or superbly sublime.

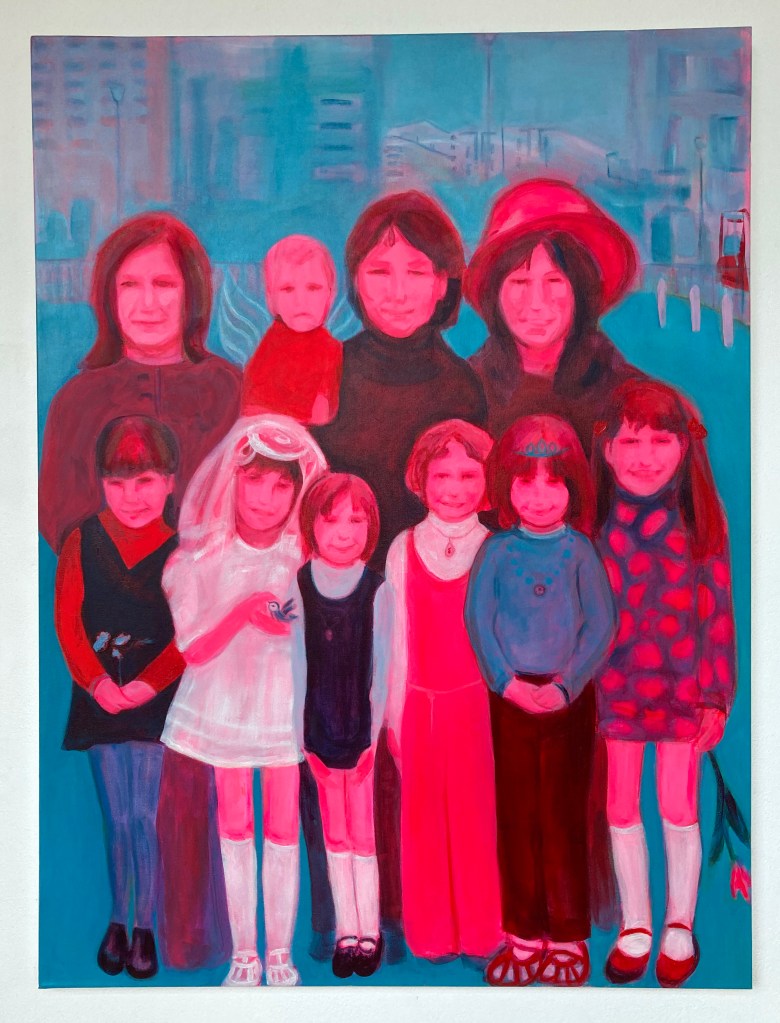

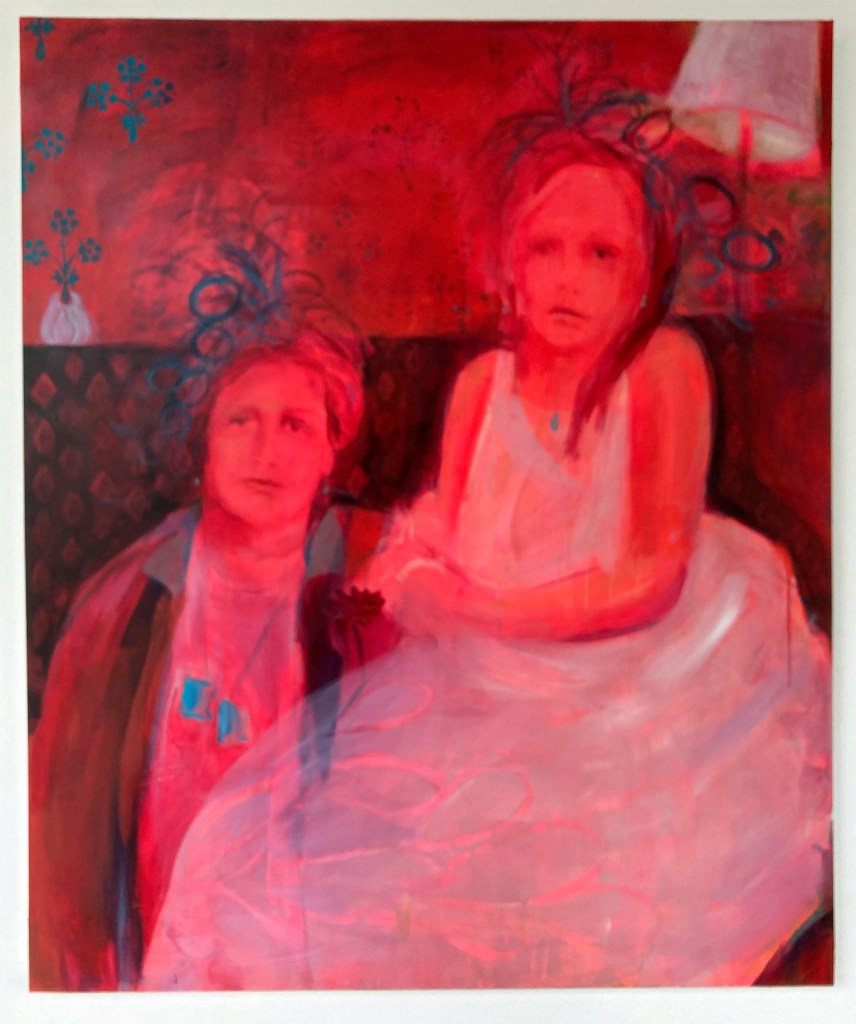

But an organisation such as the Towner pursues a positive remit to celebrate both the past and the present for a broad range of visitors. Thus, the Towner Emerging Artist Fund has supported a slightly reduced version of Dana Awartani’s exhibition, Standing by the Ruins, originally shown at the Arnolfini in Bristol earlier this year. Awartani, a Palestinian-Saudi artist now based in New York, references the craft, history and traditions of the Middle East in her broad ranging practice and applies her universal themes to the present day. This is a highly thought provoking exhibition – and I cannot see Awartani being designated as emerging for too long. She has also been chosen to show her work in the National Pavilion of Saudi Arabia in the Venice Biennale in 2026 and if you Google her name there’s much to read on-line already and this makes it unnecessary for me to echo what other writers have already written about this work.

I do not really know what others will have thought of the Towner display, particularly as I was there on the opening night before I have had an opportunity to talk to friends who have seen it for themselves. Not all exhibitions linger in the mind for too long either – but I suspect that this one will. At least it should do, even if for lamentable and distressing reasons. Sadly, but necessarily, we are aware to some degree of the religiously and politically inspired cultural and economic destruction that is going on in the wider world right now. We may well be shouting at our TV screens most nights, but I doubt we regret the choice available to switch off both literally and mentally before retiring for the evening. There might be a sense of the elsewhere that protects us emotionally. Meanwhile we can have a good old gripe about the potholes the local Council fails to fix, the frequently poor performance of our various water companies, or that yet another public library is closing due to lack of funds. If we do still manage to follow the TV news without depression and/or anger setting in too overwhelmingly (choose your own issues to be frustrated by) we can always counter this by getting out and securing an aesthetic fix from visiting an art gallery. Oddly, though positively, in Standing by the Ruins both positive and negative emotions can organically combine.

In Awartani’s work that element of visual delight, dexterity and excellence is certainly foremost, particularly in an applied design sense. The drawings and paintings for her Standing by the Ruins series in 2D and 3D outcomes, reveals an impressive level of skill in applying a traditional, age-old geometric system of drawing and pattern making employing a compass and ruler (not a digital program) into architectural references. Something that looks good draws us in. Form and content interweave.

But before being drawn to the works displayed on the walls the works that the visitor will probably notice first are three floor-based arrangements of coloured bricks that the designs on the wall back up. These are the ruins that the exhibition title references – recreated sections of the floor of the Hammam al-Samara in Gaza, one of the oldest bathhouses in the region, but which has now probably been destroyed. To enhance the notion of destruction and obliteration the bricks are cracked and well on the way to further decimation. The artist worked with a collective of adobe brick makers (craftspeople of Syrian, Afghan and Pakistani origin) and deliberately left out the binding agent (hay) so the works are purposely intended to break up.

Whilst these would-be floors are adequately placed for the visitor to walk around there is a slight sense of the possibility of tripping, though no one does. The works are clearly installed rather than functioning as sculptures. Quite soon college tutor mode kicks in for me and, if I was questioning the young maker in an end of project tutorial, I may have commented that I want to see people walk on these floor coverings. Get on trend – employ the audience as active participants. In fact, I imagine being one of them myself. I visualise seeing the piece(s) destroyed, not because I dislike the work, but because the volume of the heavily implied message might, metaphorically, be turned up. If we accept that somewhere down the line we, and the governments we elect, are all complicit to some degree in the endless tragedies of the world, we are, by implication, the destroyers too, so lets be more physically involved here. Thereafter, more bricks could be made to replace the sculpture anyway, for a never-ending sequence of works to be installed elsewhere. But this is a male response. And that’s the problem.

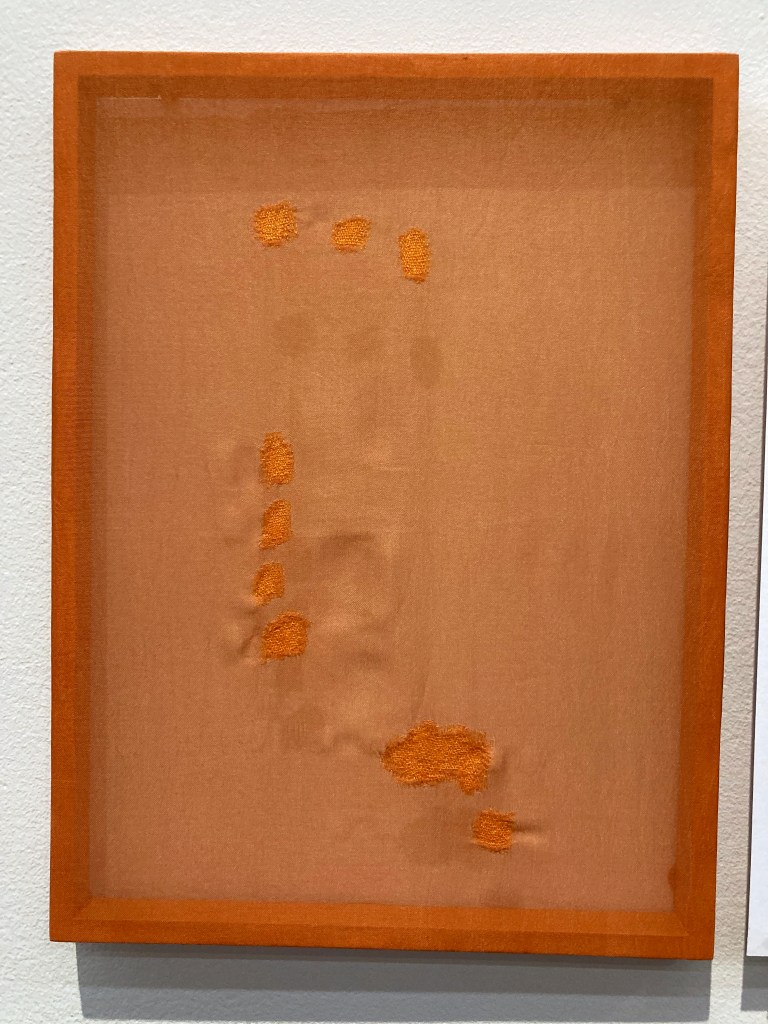

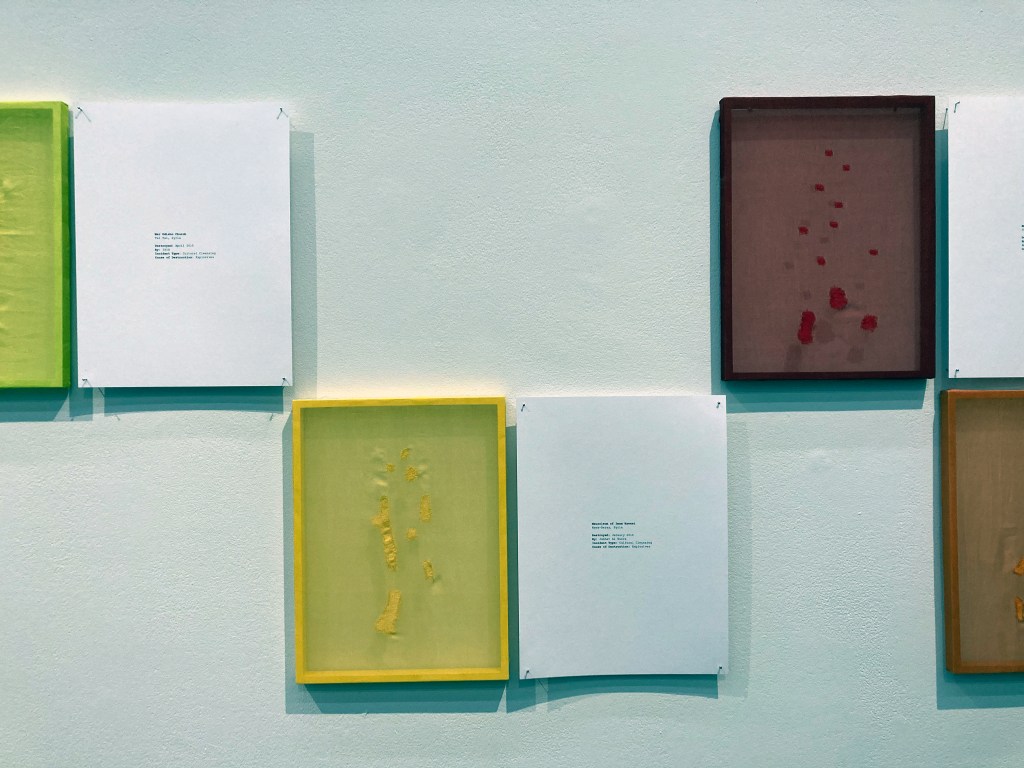

To reflect on this initial reaction, a quick summarising that has its routes in a previous modus operandi in fine art education, I was possibly thrown by that term emerging. I had too soon adopted an attitude that wanted to question and to advise this young artist. Arrogance, I know, but bear with me. My imaginary student might next have advised me to consider a set of other works displayed on the wall. These are from the Let me mend your broken bones series. In these works she has employed others to participate. Not in destroying but in making and mending by darning on medicinally dyed silk and implying a more positive attitude to life of preserving rather than wrecking. A female response – albeit embodied in hard reality.

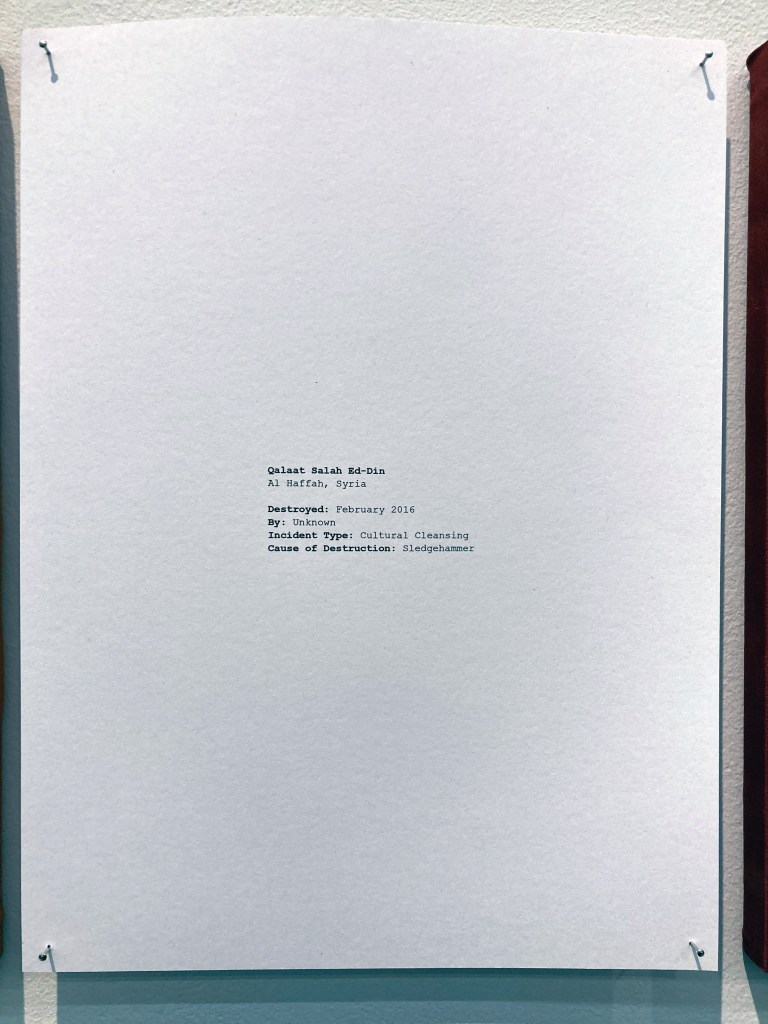

Initially the colour range might draw the observer to them, with attractive dyes of orange, red yellow and green. But get up close and we see a previously, a purposely, distressed surface that is fixed but permanently scarred. Paired paper panels display a text that records the scene’s recent history. The where, when, by whom, incident type and cause – listed methodically. Cold black text on a white background. Record keeping. Factual. Cultural cleansing is a term that terrifies and is certainly not confined to the Middle East. The interests, cultural background and broader context of an individual – such as an artist or any of the visitors to this exhibition – are always part of a much larger whole. This, of course, is stating the obvious. What may not always be so apparent or impactful is the fact that what might initially be considered as happening elsewhere, instigated by others, relates to our own history too. In a postcolonial age we now might think it’s in the past. Seeing this exhibition and letting it sink in for days after is sobering.

Standing by the Ruins is how Awartani operates. It constitutes an active positioning. Her work responds a little more quietly and contemplatively than a reactive, impulsive temperament might. The work acknowledges creation as a response to death and ruination; counters destruction with gentleness, positive even if piecemeal, literally re-making and mending. A slow and time-consuming process that is appropriate, for lives and lands are precious, and the relationship between each other and others can be far more accommodating of perceived differences. Hence the importance of landscape related themes in art from any era and of what is, and was, witnessed in various locations. So, if I might cheekily paraphrase a short statement from an essay in the catalogue* from the Impressions in Watercolour exhibition by Ian Warrell: “Turner had… contributed substantially to the transformation of perceptions of landscape subject matter…”

Dana Awartani changes our perception and understanding too.

Geoff Hands, Brighton (December 2025)

* Essay: Nature raw or cooked: Approaches to Sketching in British Landscape Watercolours by Ian Warrell, published in Impressions In Watercolour: Turner and his Contemporaries. (Holburne Museum, Bath, 2025)

Links:

The elephant in the room?

Forms of postcolonial destruction continues today, aided and abetted by super powers to the east and west – even here in Brighton where L3Harris (the sixth largest defence contractor in the USA – and the world’s largest manufacturer of precision weapons) produces parts for the F-35 fighter jets used by the Israeli government to help destroy Gaza and the Palestinians living there.